Miss T, a 21-year-old Hong Kong student, cannot forget the beating that she received from her boyfriend at the time when she told him that she wanted to end their 14-month relationship.

“I was so scared and did not know how to handle the situation,” she said. She did not want to reveal her identity, but she was willing to share her experience of physical violence, which happened during a trip to Korea in September 2019.

“He pinched me hard. I was very scared at the time and wanted to escape from him,” Miss T recalled.

“I was desperate when he squeezed my neck.

And I resisted so I wouldn’t be killed by him.”

The incident occurred when they were checking out of a hotel room. It was the first time that the boyfriend had been violent. As Miss T described the attack, after she proposed that they break up, he demanded that she return the gifts that he had given her, including the shoes that she wearing at the time. When she refused to remove the shoes, he took them from her forcibly, pushing her to the floor and squeezing her neck, legs, and arms. Her photos afterward show the bruises and scrapes that she received.

Bruising on Miss T’s arm and legs.

Miss T said that, when she was in primary school, she had been taught how to deal with child abuse, but, as an adult, she had been uncertain how to respond to the beating. In the end, she told only her friends and not the police because she did not want to have to interact with her assailant again. Also, because the incident had occurred in Korea, she was unsure whether the Hong Kong police would take her report of it.

When the young man in question later tracked Miss T down again in Hong Kong, she refused to see him, putting an end to their relationship. In the aftermath, she said, she had been afraid of falling in love and interacting with other people for a while.

Intimate partner violence is everywhere

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes intimate partner violence (IPV) as physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, or psychological harm caused by a current or former partner or spouse. IPV is a serious but preventable public health problem. It can occur among heterosexual or same-sex couples and may not be associated with sexual intimacy.

In Hong Kong as elsewhere, women and girls naturally constitute the vast majority of the victims of IPV. Specifically, according to data from the Social Welfare Department, more than 80% of victims over the past seven years were female. Among these victims, physical violence was the most common form of abuse, accounting for around 80% of total IPV cases each year.

The Social Welfare Department’s data show further that the number of IPV cases reported has declined over the past seven years. Fiona Wu Kai Yan is a part-time lecturer in Hong Kong Baptist University’s Department of Social Work and also works as a social worker specializing in male victims of IPV. She believes that the cases reported by the department represent just the tip of the iceberg with respect to the actual frequency of IPV. Among female victims, Miss T is an example of this underreporting in that she did not seek help from the police or social workers, so her case went unrecorded.

Increasing numbers of male victims of IPV

Though, as noted, most IPV victims are female, the number of recorded male victims has been rising. In fact, the proportions of male and female victims in Hong Kong have fluctuated over the past TIME PERIOD (Chart: Gender of Victims). Wu said that it had likewise been her professional experience that the number of requests for help from men who have suffered from IPV has been increasing in Hong Kong.

From 2017 to 2019, the Social Welfare Department distributed commercial advertisements, posters, and leaflets and held a series of events in an effort to raise awareness of IPV and measures to combat it. Furthermore, some NGOs, such as Harmony House, have launched initiatives focused on men and boys involved in IPV. Such initiatives have raised awareness in the broader society of male IPV victims and encouraged men to seek help.

“In my experience, there are more young males in their 20s to 30s seeking help from us,” said Iris Yu Hang Laam, a counselor with HE@T (Healing and Empowerment at Network and Technology), as the Harmony House initiative targeting male victims is called. “Most of them have a higher education background, like undergraduate or master’s degrees, or they are even the managers of companies.”

Same sex IPV

In Hong Kong, fewer than 20 cases of IPV involving same-sex relationships have been recorded by the Social Welfare Department annually in recent years. This relatively small number does not, however, reflect the reality of intimate violence in this context. Thus, Wu observed that “Relatively speaking, non-heterosexual intimacy violence is more serious, but victims rarely ask for help. One of the reasons is that there are few non-heterosexual-friendly institutions.”

The incidence of IPV has increased significantly during the pandemic

Harmony House, Rainlily, a Hong Kong anti-violence resource center, and the Women’s Foundation released a joint statement about an increase in the reports of domestic violence during the pandemic on April 24, 2020. The organization reported a 25% increase in reports on its hotline from January to March in 2020 and Rainlily a 30% increase on its hotline over March 2020.

Likewise, the Hong Kong Federation of Women’s Centres reported receiving 34 domestic violence-related requests from January to March 2020, compared with 16 such requests in the same period in 2019.

“According to the Social Welfare Department’s data, there were more IPV cases in 2008 because of the financial crisis,” noted Gabriel Chan Pui Yan, HE@T’s project manager. “At that time, the economy in Hong Kong turned bad, and the unemployment rate increased, which means a lot of people lost their jobs and their financial support. Hence, there were more conflicts between the couples or family members, and then the violence happened.”

Data from the Census and Statistics Department and Social Welfare Department indicate that the trends in the unemployment rate and number of IPV cases, respectively, were roughly parallel from 2007 to 2019. Thus, in 2008, there was a sharp increase in unemployment and in the number of IPV cases because of the financial crisis. This is the situation that Chan described.

The link between increasing IPV and the pandemic is that people have been forced to stay at home frequently and that, as a result of spending more time with their intimate partners, are more likely to argue with them, especially about finances since so many are unemployed. Too often, arguments lead to violence. Further, the pandemic may cause some victims of IPV to be reluctant to venture out to seek help. For all of these reasons, the actual incidence of IPV in Hong Kong may be higher than in previous years.

The causes of IPV

Human relationships, including between the members of a couple, are bound to involve conflicts and miscommunication at times. According to the British medical journal The Lancet, violence in such situations is best understood as a strategy for resolving conflict. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists four categories of risk factors for IPV relating to the individuals involved and the nature of their relationship, the community, and the broader society. In particular, relationship and community factors can be targeted in efforts to prevent IPV.

The Hong Kong government has resources for protecting the victims of IPV, including shelters, legal support, and professional counseling. However, “There are not enough public resources providing for the victims of IPV” according to Gabriel Chan, a project supervisor with Harmony House.

Another key factor is education: it is necessary to teach children how to build relationships with others in ways that foreclose the opportunities for IPV in the future. Thus, Fiona Wu asserted that “Although there is more gender education now, it is still not enough.”

The current policies relating to IPV in Hong Kong

Shelter services

The Hong Kong government has officially recognized five shelters—Harmony House, Serene Court, Wai On Home for women, Sunrise Court, and Dawn Court—that provide temporary haven for the victims of IPV and their children who are facing a crisis. Most offer their services to women and children only. The addresses are kept confidential in order to protect the clients.

Iris Yu, a counselor with Harmony House, described the current situation in Hong Kong as inadequate. “At Harmony House, we have two shelters, one each in the Kwun Tong and Kwai Tsing Districts. We know that some people think that the shelters are too far from their homes for them to seek help.”

Thus, in a city the size of Hong Kong, five shelters are simply not enough to ensure that all victims of IPV are able to access shelter services without having to travel long distances or overcome other obstacles.

Updating the guidelines

The government updated its Procedural Guide for Handling Intimate Partner Violence Cases in 2011. This document established the guidelines for various government departments and organizations in handling cases of IPV. Thus, the guide was consulted by the Department of Health, Hong Kong Police Force, Legal Aid Department, Department of Justice, Schools, Housing Department, and similar agencies. The guidelines for social welfare service units were updated in 2014 to include IPV involving same-sex relationships.

“From a broad perspective, Hong Kong does not have comprehensive support facilities, like shelters for the victims,” said Harmony House’s Gabriel Chan. “Also, the Social Welfare Department does not set up a specialized group for handling the male victims in IPV cases, and there is not enough education for citizens on the issue of preventing IPV.” Thus, despite the recognition of the trend of more male victims suffering from IPV in Hong Kong, there are as yet few male-friendly organizations from which they can seek help. Chan suggested that that the Social Welfare Department may, in light of an overall decline in the number of IPV cases in recent years, consider the resources currently allocated to IPV prevention and treatment to be sufficient.

Sex Education in Hong Kong

According to the World Health Organization, the purpose of sex education is “to develop and strengthen the ability of children and young people to make conscious, satisfying, healthy and respectful choices regarding relationships, sexuality, and emotional and physical health.” This form of education does not encourage teenagers to have sex but rather helps them to understand how to build good relationships with others and to respect with their partners.

Sex education in Hong Kong is based on the Guidelines on Sex Education in Schools compiled in 1997 by what was then the Education Department and is now known as the Education and Manpower Bureau.

Various organizations, as well as members of the legislative council such as the Honourable Mrs. Sophie Leung, have proposed updating the guidelines, but the government has insisted that they are meant only as a reference for schools, for instance asserting in 2006 that they “should not be regarded as a curriculum guide which is normally drawn up for academic subjects.”

In 2018, the Research Office Legislative Council Secretariat prepared an information note for sexuality education in Hong Kong. Observing that 1997 The Guidelines on Sex Education in Schools were still in use, the secretariat proposed integrating sex education into the Moral and Civic Education curricula of the key learning areas or subjects in primary and secondary schools.

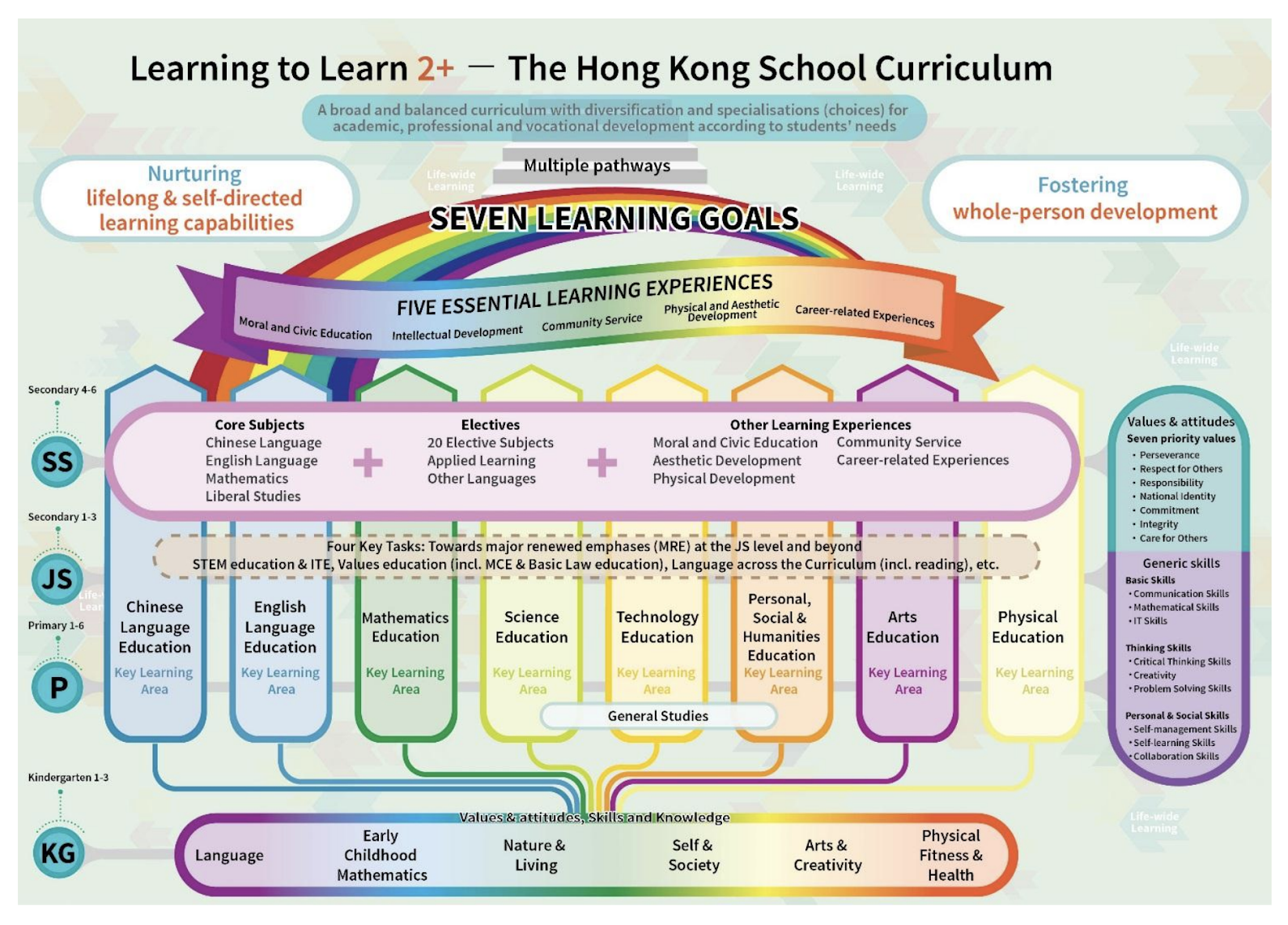

The primary school and secondary curricula in Hong Kong’s schools

Source: Secondary Education Curriculum Guide Draft (May 2017) Booklet 2 Learning Goals, School Curriculum Framework and Planning (https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/renewal/Guides/SECG%20booklet%202_en_20180831.pdf)

The Education and Manpower Bureau supplied the latest frame draft of the curricula for primary and secondary schools. As can be seen in the above figure, sex education, rather than being a specific subject for either primary or secondary students, takes the form of a flexible curriculum that schools arrange according to their specific circumstances.

Sex education is also included in the key learning area of General Studies for primary school students and that of Life and Society, Science, and Home Economics/Technology and Living for junior secondary students. This curriculum in addition forms part of Liberal Studies in a core course, Biology, Ethics and Religious Studies, Technology, and Living, and of Health Management and Social Care. These are elective courses for senior secondary students.

Thus, while sex education is included in various courses, it is not the sole focus of any one course. Various aspects of the subject are also discussed in science classes, for instance in the context of animal physiology. In any case, the amount of time devoted to the subject has been decreasing, as the above charts show.

Miss Wu, the social worker serving male victims in domestic violence, and Miss T, the victim of physical violence, were both of the opinion that there is not enough sex education in Hong Kong’s schools.

“The education in Hong Kong does not teach students well how to connect with our body and emotional control and so on,” said Miss Wu. “This means that, when people are angry, they fight other people and get out of control. What I have learned came too late to help in my case.”