“If a woman says she likes sex, does that mean she likes being raped?” asked Winnie Wong Wai Yin, a fourth-year film student at Hong Kong Baptist University.

Wong said that she had experienced sexual harassment on multiple occasions, recalling one incident when she was in secondary school.

“I was on my way home from school and took the MTR from

Kowloon Tong station to Tai Wai. I was listening to music, so I wasn’t paying much attention to my

surroundings. Suddenly, I noticed something rubbing against my dress and at first thought it might

be some lady’s carry-on. Still, it felt odd, as the ‘touch’ was rhythmic. When I turned around, I

saw a man behind me,” Wong recollected. “I was so startled that I just stared at him instead of

reacting, and then I immediately left the train.

“I was on my way home from school and took the MTR from

Kowloon Tong station to Tai Wai. I was listening to music, so I wasn’t paying much attention to my

surroundings. Suddenly, I noticed something rubbing against my dress and at first thought it might

be some lady’s carry-on. Still, it felt odd, as the ‘touch’ was rhythmic. When I turned around, I

saw a man behind me,” Wong recollected. “I was so startled that I just stared at him instead of

reacting, and then I immediately left the train.

“I am furious and regret that I didn’t report the incident at the time. There may be other girls who have suffered the same sexual harassment that I have but also did not report it,” observed Wong.

An analysis of news reports about sexual violence at MTR stations by various Hong Kong media outlets over the past six years showed that sexual violence occurred frequently at the Admiralty and Prince Edward Stations, at each of which nearly 30 incidents were reported, as well as the Wan Chai and Kowloon Tong Stations.

Under a government policy emphasizing rail transport, the MTR is the most common way to get around Hong Kong, with over 5 million trips occurring on an average weekday. Thus, according to one study, the Island, Tsuen Wan, and East Rail Lines each had over 1 million riders on weekdays in the period from September 1 to 27, 2014.

The MTR is not the only place where Wong has been sexually harassed, with other incidents occurring on the bus and a bike path.

In such instances, those who experience sexual harassment are often blamed for it. Wong recalled that, when she sought help from a friend after one incident, “She told me not to wear a short skirt to minimize the chances of sexual harassment.” She was disappointed with this response. “Just because I’m keen to wear short skirts and drink with my friends until midnight, does that mean it’s justified for a man to sexually assault me? It’s ridiculous.”

Winnie Wong is not shy about sharing her experiences of sexual harassment. (Credit: Data Story)

Wong felt that victims were becoming increasingly willing to open up about their experiences with sexual harassment following the social movement last year and that there were some downsides to the visibility of the issue. “I think there are more people who encounter sexual harassment,” she explained. “Because the police aren’t trusted by certain individuals—like me—people who are thinking about it [committing sexual assault] may think we won’t report it even if we’ve been harmed, so they may not suffer any consequences.” She was, therefore, worried that the problem would grow worse.

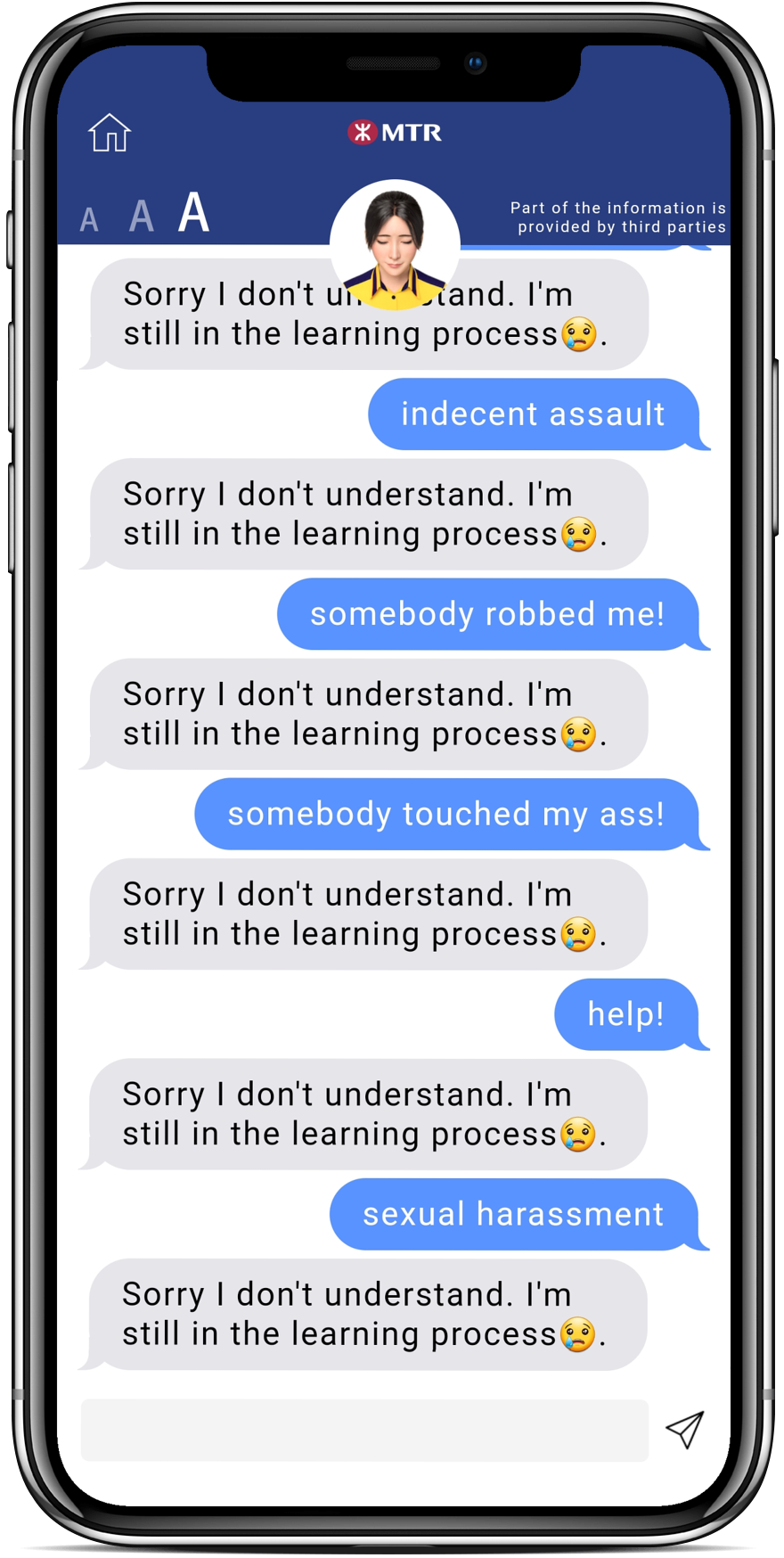

Wong suggested that the government should increase the penalties for crimes committed in MTR stations and that non-profit organizations could post flyers and signs encouraging children to speak up and ask for help immediately if they suffer abuse. In her experience, Wong said, she had felt that there was nothing she could do about it after being harassed.